Forensic Animation with 3D Computer Graphics

Note – This is an article on forensic animation written by Jim Lammers and published in the Kansas City Metro Bar Association’s magazine KC Counselor in September of 2004.

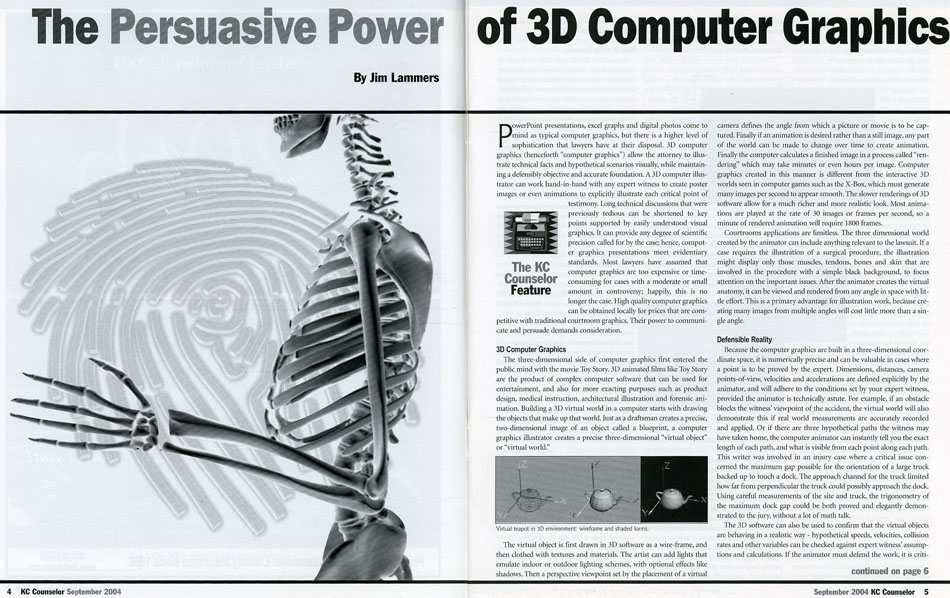

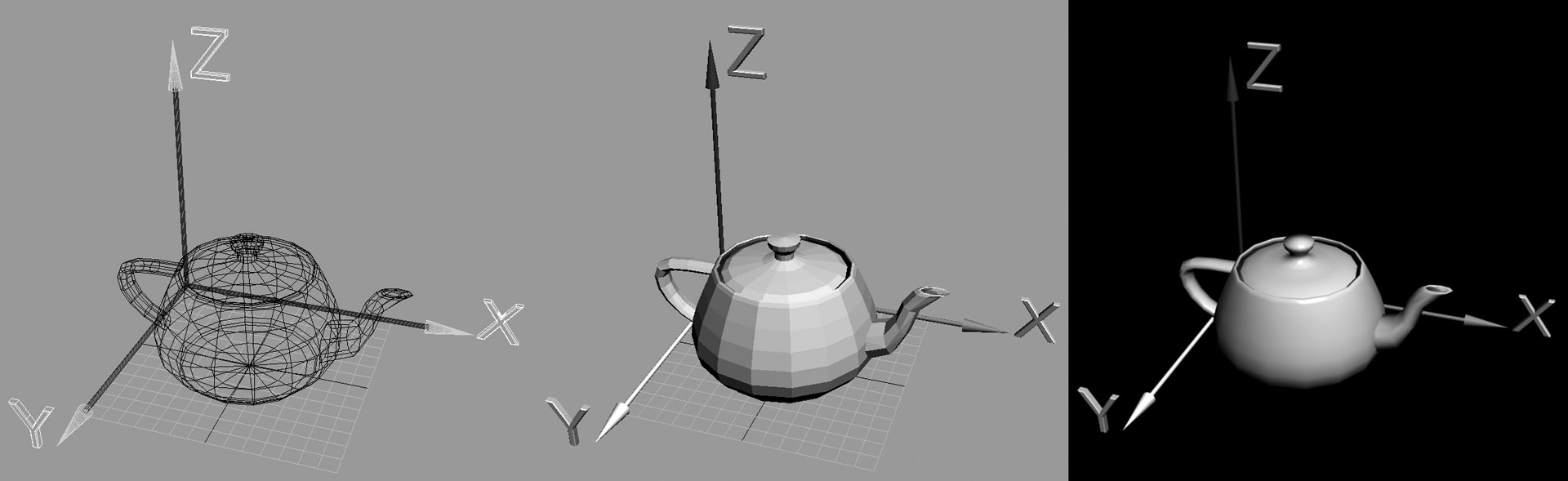

Powerpoint presentations, excel graphs and digital photos come to mind as typical courtroom computer graphics, but there is a higher level of sophistication that lawyers have at their disposal. 3D Computer graphics (henceforth “computer graphics”) allow the attorney to illustrate technical facts and hypothetical scenarios visually, while maintaining a defensibly objective and accurate foundation. A 3D computer illustrator can work hand-in-hand with any expert witness to create poster images or even forensic animations to explicitly illustrate each critical point of testimony. Long technical discussions that were previously tedious can be shortened to key points supported by easily understood visual graphics. Computer graphics presentations can also meet evidentiary standards. Most lawyers have assumed that computer graphics and forensic animations are too expensive or time-consuming for cases with a moderate or small amount in controversy; happily this is no longer the case. High quality computer graphics can be obtained locally for prices that are competitive with more traditional graphics.

Courtroom applications are limitless. The three dimensional world created by the animator can include anything relevant to the lawsuit. If a case requires the illustration of a surgical procedure, the illustration might display only those muscles, tendons, bones and skin that are involved in the procedure with a simple black background, to focus attention on the important issues. After the animator creates the virtual anatomy, it can be viewed and rendered from any angle in space with little effort. This is a primary advantage for illustration work, because creating many images from multiple angles will cost little more than a single angle.

DEFENSIBLE REALITY

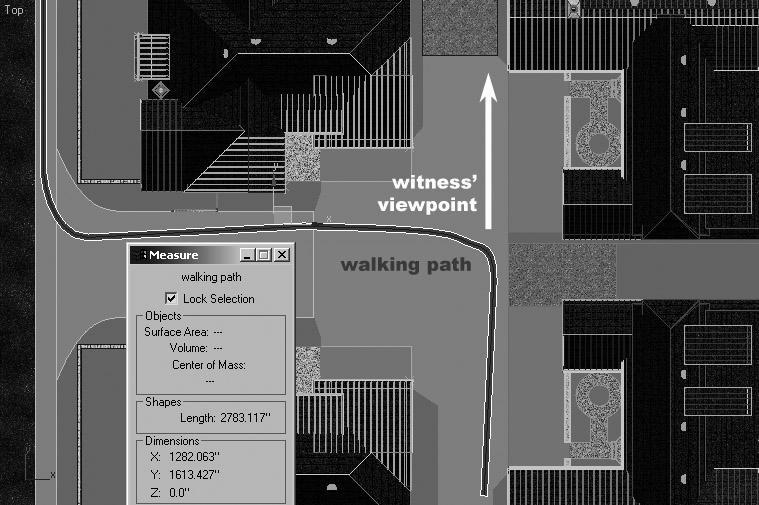

Because the computer graphics are built in a three-dimensional coordinate space, it is numerically precise and can be valuable in cases where a point is to be proved by the expert. Dimensions, distances, camera points-of-view, velocities and accelerations are defined explicitly by the animator, and will adhere to the conditions set by your expert witness. For example, if an obstacle blocks the witness’ view of the accident, the virtual world will also demonstrate this if real world measurements are accurately recorded and applied. Or if there are three hypothetical paths the witness may have taken home, the computer animator can instantly tell you the exact length of each path, and what is visible from each point along each path.

This writer was involved in an injury case where a critical issue concerned the maximum gap possible for the orientation of a large truck backed up to touch a dock. The approach channel for the truck limited how far from perpendicular the truck could possibly approach the dock. Using careful measurements of the site and truck, the trigonometry of the maximum dock gap could be both proved and elegantly demonstrated the jury, without a lot of complex math.

The 3D software can also be used to confirm that the virtual objects are behaving in a realistic way – hypothetical speeds, velocities, collision rates and other variables can be checked against an expert witness’ assumptions and calculations. If the animator must defend the work, it is critical that the animator is a mathematically astute expert in his or her own right. Their testimony may be called for, to support the contention that the computer model is an accurate representation of the substantive experts’ testimony.

Computer images of a 3D scene may be taken from any point in time, and from any point in space. It may best serve the case to show one instant of an industrial accident from three different angles. Or it may be better to show a sequence of four images from a single angle in half-second increments. These are critical choices that the lawyer must consider and then direct the animator to produce for the case.

This author produced a series of images for a patent dispute, showing how the bones of a foot might line up with parts of a shoe. A 3D model of a foot skeleton allowed for easy illustration of various bone poses and positions relative to the shoe parts. Top and side views for each pose and position were created, and the project was inexpensive for the client since Trinity’s stock model library collection already included a fully detailed foot skeleton.

VISUAL STYLE AND ADMISSIBILITY

While admissibility is the domain of the attorney, the animator can assist by making sure that the virtual objects, including virtual people, are presented as simply and in as non-prejudicial manner as possible. For example 3D human models in forensic animation will generally omit detailed facial features. Many times an attorney will choose a gray, fairly flat appearance for the model’s face giving a racially neutral impression. There is a cost to this approach – omitting details from crucial objects reduces the realism of the images and consequently their visual impact and persuasive power. In the end, this is a judgment that must be made by the attorney with the animator providing technical assistance and a wide range of options for each presentation.

IMAGES VS. MOVIES

There is no limit to the virtual objects that can be created to fill a virtual world or virtual environment, other than computer resource limits. After all the objects in a virtual world have been built, the animator can capture images of the virtual environment in all the same ways a real world photographer can capture snapshots or record movies. The attorney can choose to take a series of snapshots from critical angles, or she may choose to generate a movie that carries the viewer from one point to another inside the virtual environment. As noted earlier, an animation or movie is simply a large number of sequential still images or frames. Each image is a digital computer file comparable to the images created by a hand held digital camera. This means that the attorney enjoys tremendous flexibility in the method used to display these images.

This wealth of choices demands the exercise of judgment by the attorney. Cost is certainly an important factor – even if the budget is generous, animations require more planning time and more computational time than still images. Other factors which should be considered include: the preference of the particular judge, the sophistication of the courtroom equipment, and the lawyer’s comfort level with the technology used to display the images. Another factor is to consider that animations are more immersive, dynamic and interesting than a static printed poster; however they may only be played once or twice. A poster will often be visible to the jury for hours or days during the trial. It can act as a silent advocate for the case.

TIME IS OF THE ESSENCE

Animations unfold over time, and may be the best choice in cases where the argument relates to a sequence of critical events. A time display in the corner of the screen can be helpful in creating a readable transcript and a clear verbal argument. For example it may be possible to point out that exactly 21 seconds after a critical point in the animation, the right front wheel of the plaintiff’s car left the pavement. Time can also be manipulated to demonstrate important facts. An animation may be played at a fractional speed to allow the jury to absorb all the events occurring simultaneously. Another useful approach is to play the same sequence of events as seen from different physical viewpoints. The animation can be stopped or frozen at critical points in the timeline and the views of different witnesses at that particular point in time can be compared.

NUTS AND BOLTS ON THE DAY OF TRIAL: RECOMMENDED APPROACH

Using courtroom animations adds the burden of managing courtroom playback and presentation. The best approach is to use a laptop computer playing back a computer movie and using a bright LCD type projector to play it on a large white piece of foam core, or a white wall if available. Computer movie formats must be encoded by the animator in a way that keeps the images clear and allows jumping to any point in the movie via the time slider. Computer movies are preferable to DVD because the attorney can more easily move the time slider back and forth to illustrate verbal points in his presentation. Generally, a complete animation will run for only a minute or two, but the attorney may want to present and discuss it for a much longer period of time.

HIRING AND WORKING WITH A COMPUTER GRAPHICS ARTIST

As with any illustration, the work product of an animator has to be endorsed by a witness, most frequently an expert witness. An attorney who considers using computer animation should consult with the animator as soon as the testimony of the endorsing witness has been recorded in a definite form. This may occur after an expert witness has submitted a summary of his investigation and conclusions. The attorney should consider whether she wishes the images, models or animation to be available during the deposition of her expert. In any event, the attorney should get supporting documents and information to the animator as soon as possible.

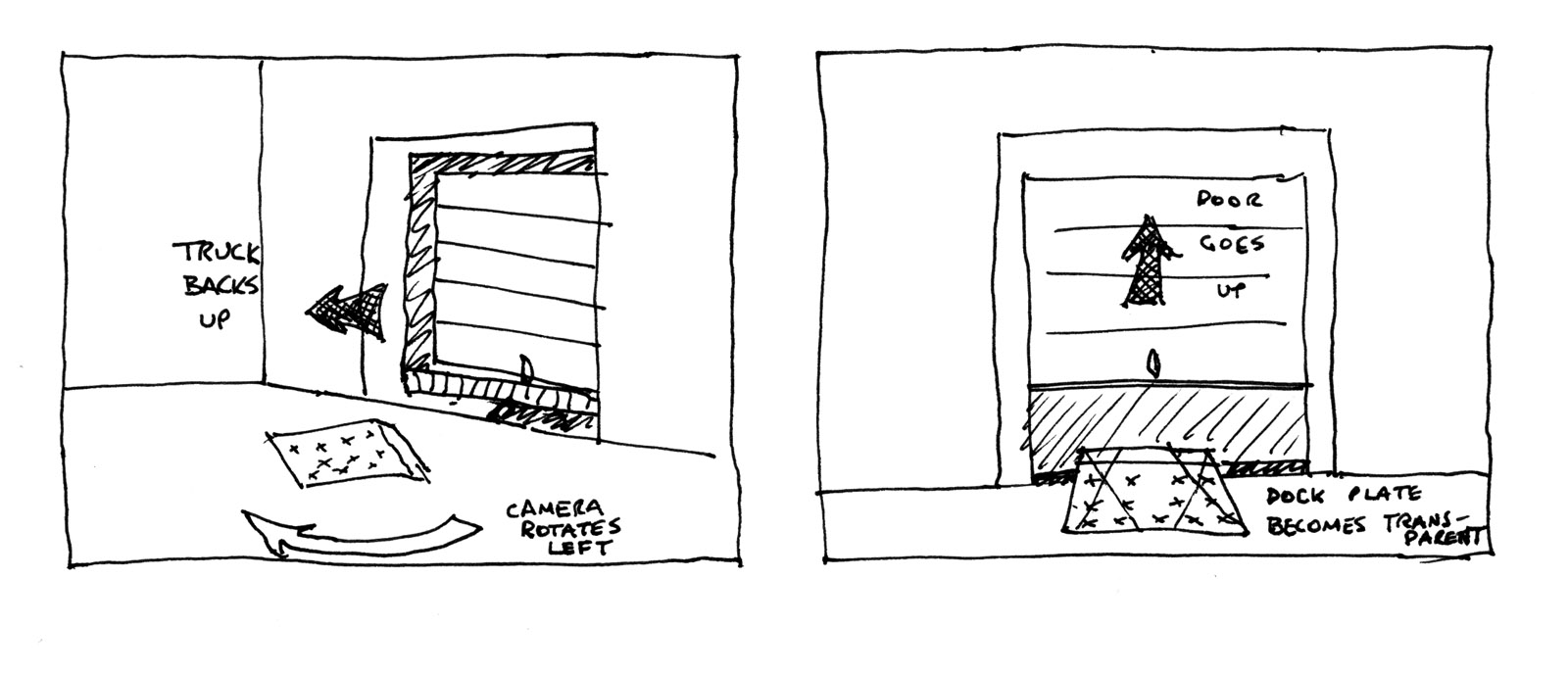

Storyboards are a tool that can be used by attorneys to save time and money and streamline the process of producing an animation. When a storyboard is completed it looks like a crude comic book, containing the sequence of images the attorney wants the animator to create. Even if the attorney’s drawing skills are limited, creating a storyboard before work on the animation has begun will prove very cost-effective. The animator can then discuss any special challenges presented by the proposed animation and he may well be able to suggest simpler or more effective methods to communicate the same ideas.

For an explanatory animation (as opposed to a forensic animation), the attorney should try to think like a movie director. Where should the virtual camera be placed to best tell the story? In many cases it is good to avoid a flat, 2D presentation where things happen in front of a stationary camera. It’s often better if the camera moves around just as a person operating a camcorder would explore a scene. Additionally, it usually adds little cost to add some graphical or text overlays to your animation. Consider the addition of sub-titles, on-screen measurements, time counters or anything else that helps make the animation clear. For example, an important object in the image can temporarily glow to call the viewer’s attention.

COUNTERING THE FORENSIC ANIMATION OFFERED BY AN OPPONENT

As computer graphics become cheaper and more popular, trial counsel need to be prepared to respond to an opponent who offers an animation in support of his case. First, the purpose of the animation must be clarified. Is it solely intended to explain a scientific process such as DNA testing or fingerprinting? If so, the offering attorney should be able to identify an expert witness who can affirm the accuracy and relevance of the animation. Is the animation intended to re-create the central events giving rise to the lawsuit? If so, a copy of the images and/or animation and the underlying scene file used to create them should be requested by the responding attorney. The scene file is the computer file that contains all the actual project data, and will be specific to the 3D software the animator has used.

The scene file can then be submitted to a consulting animator for analysis and testing of critical values. The animator used by the offering attorney may have muddled enough critical values (and left them unchecked by his expert witness) to completely undermine the validity of the animation. For example, a viewpoint representing that of a witness may be set a foot higher than that person’s actual eye-height, or a telephone pole may be in reality positioned far closer to the edge of the road than represented in the animation. Some self-described forensic animators have no technical training or skills at all, and are basically self-taught artists. There is no recognized certification program for a forensic animator.

Another angle of attack is prejudicial choices made in a forensic animation. Anything that is emotionally provocative should be blocked. Forensic animations of people often include hairstyle, obvious female/male characteristics and other evocative features that can subtly mislead a jury into thinking they are watching a recording of something that actually happened, rather than an animated re-creation that may be built on assumptions. A recent murder trial involving a police detective named Michael Serge included animation based on the government’s theory of the case alone. The defense claimed that it could not afford a counter animation. The government’s animation included an obvious representation of the bald, male defendant and a clearly identified female victim wearing pajamas. It was argued that this level of specific detail, tied to actual known parties, added unsupported weight to the hypothetical scenario. Details about this case can be found online in this article from CBS’ 48 Hours.

It should be noted that if changes are demanded, the task of re-rendering the animation after editing out identifying details is usually a minor cost.

CONCLUSION

Computer graphics offers attorneys an inexpensive and powerful visual tool that most have yet to harness. Where traditional illustrations were helpful, computer graphics (or forensic animation) offer at comparable price the additional benefits of easy revision and nearly free multiple viewpoints. Going beyond illustrations, 3D computer graphics can also offer animated scenarios with perfectly repeatable and mathematically exact representations of reality. Costs for animation vary but are well in the range of the prices for other presentation materials and expert witnesses, and the attorney can control costs by planning the animation or image and setting a budget at the outset. The simplicity required for the look of forensic animation also helps keep the price low. In the right situations, computer graphics can be the persuasive “hammer” that pounds in the witness’ testimonial “nail.”

Jim Lammers is President of Trinity Animation, a Lee’s Summit based firm that has provided forensic animation and graphics to clients worldwide since 1994. Lammers holds a bachelor of Science degree in Electrical Engineering from the University of Missouri. Trinity Animation has created forensic animations for several leading law firms including the Wichita office of Wallace, Saunders, Austin, Brown & Enochs. He is also the author of several books on animation for Pearson Publishing.